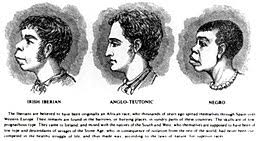

Today we discussed the New Negro Renaissance’s cultural response to cultural racism, represented by in popular culture and scientific scholarship. While scientific racism permeated different disciplines, especially anthropology, it was also made popular among the educated by Madison Grant. Here Grant, in his article “The Racial Transformation of America” published in the North American Review in 1924, discusses the consequences of the both the “negro problem” and the “immigrant problem” in the United States. Grant, and other people involved in the eugenics movement, played a key were in shaping U.S. ideas about immigrant and especially the Immigration Act of 1924.

While these arguments about biological determinism might seem like the debates of the early 20th c., unfortunately, these kinds of discussions that employ “scientific” reasons to explain the behavior of entire groups continue to be discussed among scientists. The same kinds of claims are akin to the statistic claims of black criminality, as historian Khalil Muhammad notes, employed by some white nationalists, presently.