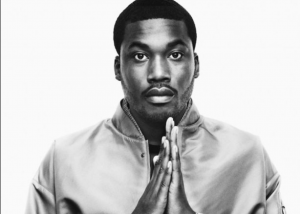

Tuesday afternoon, after five months of incarceration, Meek Mill was finally released. The popular rapper had been held since late November as a result of a failed drug test and violating the travel restrictions of his probation. Mill had violated his probation several times and Judge Genece E. Brinkley, who had overseen Mill’s probation over the years, was clearly fed up with the rapper’s antics and sentenced him to 2-4 years in prison. Immediately, there was outrage among Meek’s associates and passionate fans. After months of silence along with protests, and unrest, Mill was finally released Tuesday and immediately made his presence felt with an appearance at the Philadelphia 76’ersplayoff game; where fans showed heavy support for Philadelphia native.

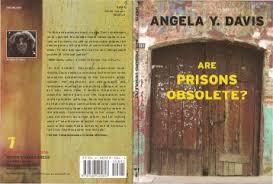

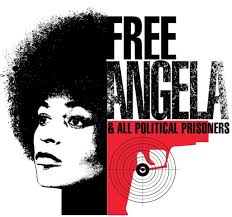

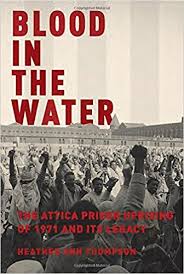

Although Meek’s release shows the power of the people in the face of injustice, it also highlights a much larger issue in America. Mass incarceration, especially that of African Americans, is a result of the flawed American criminal justice system. After his release, Meek tweeted, “I understand that many people of color across the country don’t have that luxury and I plan to use my platform to shine a light on those issues.” As a result of his release, he has the chance to make a huge impact on an issue that is talked about enough. The corruptedness of the prison system in America is obvious and when taking a close look at mandatory minimums, probation violations, and a multitude of other issues. The possibilities of Meek’s opportunity is endless. He could back bail funds, and team up with organizations like Black Lives Matter to spearhead campaigns to fund the release of black men and women in prisons across America. He could start his own social campaign and make an impact within the city of Philadelphia. He could make a documentary or write a book, and give outsiders a first-hand look at the flaws in our prison system and the struggles that one must go through to see the light of day again as a free man or woman. All things considered, Meek must carefully think about the steps he is going to take to make an impact on the lives of African Americans in the present and for the future.

Meek Mill And Mass Incarceration: How Rapper Can Work To Help The Movement